I spoke about the different jatis, the work allotted to each of them and the rites and customs prescribed for each. What I said was not entirely correct. The vocation is not for jati; it is jati for the vocation. On what basis did the Vedic religion divide the fuel sticks (that is, the jatis) into small bundles? It fixed one jati for one vocation. In the West economists talk of division of labour but they are unable to translate their ideas into practice. Any society has to depend on the proper execution of a variety of jobs.

It is from this social necessity that the concept of division of labour arose. But who is to decide the number of people for each type of work? Who is to determine the proportions for society to function in a balanced manner? In the West they had no answer to these questions. Everybody there competes with everybody else for comfortable jobs and everywhere you find greed and bitterness resulting from such rivalries. And, as a consequence of all this, there are lapses from discipline and morality.

In our country we based the division of labour on a hereditary system and, until it worked, people had a happy, peaceful and contented life. Today even a multimillionaire is neither contented nor happy. Then even a cobbler led a life without cares. What sort of progress have we achieved today by inflaming evil desires in all hearts and pushing everyone into the slough of discontent? Not satisfied with such "progress" there is talk everywhere that we must go forward rapidly in this manner.

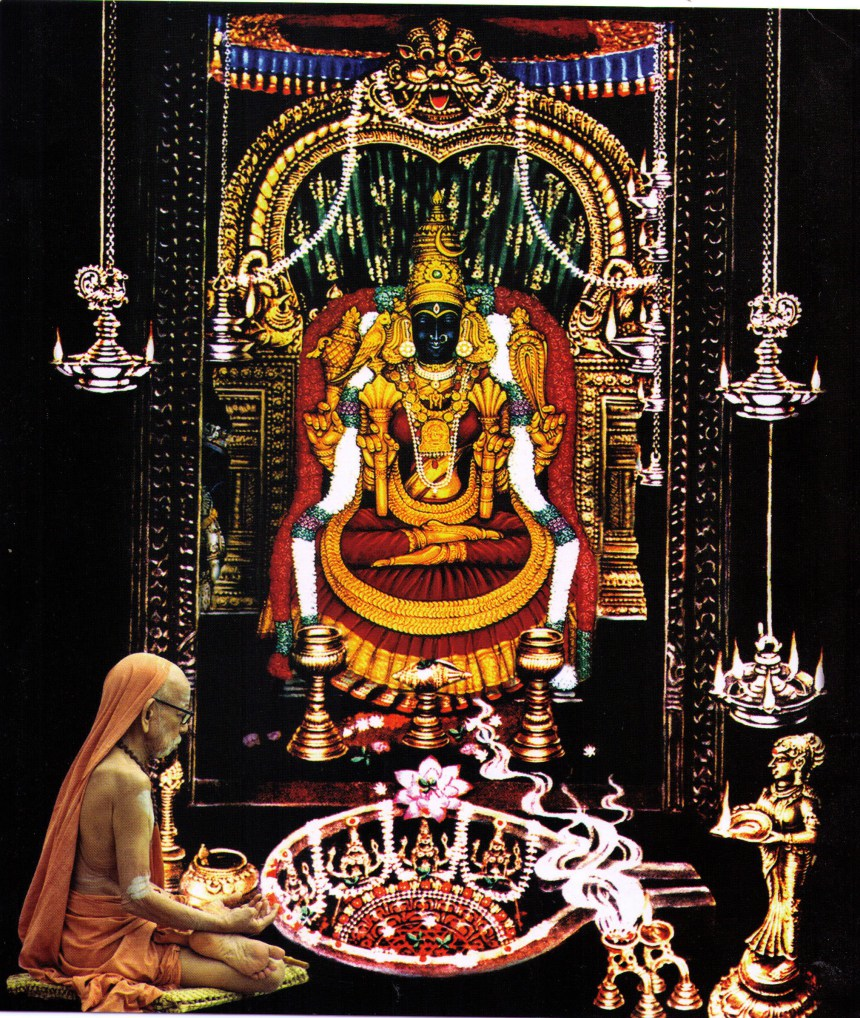

Greed and covetousness were unknown during the centuries when varna dharma flourished. People were bound together in small well-knit groups and they discovered that there was happiness in their being together. Besides they had faith in religion, fear of God and devotion, and a feeling of pride in their own family deities and in the modes of worshipping them. In this way they found fullness in their lives without any need to suffer the hunger and disquiet of seeking external objects. All society experienced a sense of well-being.

Though divided into a number of groups people were all one in their devotion to the Lord; and though they had their own separate family deities, they were brought together in the big temple that was for the entire village or town. This temple and its festivals had a central place in their life and they remained united as the children of the deity enshrined in it. When there was a car festival(rathotsava) the Brahmins and the people living on the outskirts of the village[the so-called backward classes] stood shoulder to shoulder and pulled the chariot together. We wonder whether those days of peace and harmony will ever return. Neither jealousy nor bitterness was known then and people did not trade charges against one another. Everyone did his job, carried out his duties, in a spirit of humility and with a sense of contentment.

Considering all this, would it be correct to say that Hinduism faced all its challenges in spite of the divisions in society? No, no. Such a view would be totally wrong. The fact is that our religion has survived as a living force for ages together because of these very divisions. Other great religions which had but one uniform dharma for all have gone under. And there is the fear that existing religions of the same type might suffer a similar fate. What has sustained Hinduism as an eternal religion? We must go back to the analogy of the fuel sticks. Like a number of small bundles of sticks bound together strong and secure-instead of all the individual sticks being fastened together-Hindu society is a well-knit union of a number of small groups which are themselves bound up separately as jatis, the cementing factor being devotion to the Lord.

Religions that had a common code of duties and conduct could not withstand attacks from within and without. In India there were many sets of religious beliefs that were contained in, or integrated together with, a common larger system. If new systems of beliefs or dharmas arose from within or if there were inroads by external religious systems, a process of rejection and assimilation took place: what was not wanted was rejected and what was fit to be accepted was absorbed. Buddhism and Jainism sprang from different aspects of the Vedic religion, so Hinduism(later) was able to digest them and was able to accommodate many other sets of beliefs or to make them its own. There was no need for it to treat other systems as adversaries or to carry on a struggle against them.

After the advent of Islam we adopted only some of its customs but not any of its religious concepts. The Moghul influence was felt to some extent in our dress, music, architecture and painting. Even such impressions of the Muslim impact did not survive for long as independent factors but were dissolved in the flow of our Vedic culture. Also the Islamic impact was largely confined to the North; the South did not come much under it and stuck mostly to its own traditional path.

Later, with the coming of the Europeans, faith in the Vedic religion began to decline all over India, in North as well as South. How did this change occur? Why do all political leaders today keep excoriating the varna system, giving it the name of "casteism"? And how has the view gained ground everywhere that the division of jatis has greatly hindered the progress of the nation? And why does the mere mention of the word jati invite a gaol sentence?

I shall tell you later, as best I can, about who is responsible for this state of affairs. For the present let us try to find out why some people want to do away with varna dharma. To them it seems an iniquitous system in which some jatis occupy a high status while some others are pushed down to low depths. They want all to be raised to the same uniform high level.

Is such a step possible or practicable? To find an answer, all that we have to do is to examine conditions in countries where there is no caste. If there were no distinctions of high and low in these lands, we should see no class conflicts there. But in reality what do we see? People in these countries are divided into "advantaged" and disadvantaged" classes who are constantly fighting between themselves. A true understanding of our religion will show that in reality there are no differences in status based on caste among our people. But let us for argument's sake presume that there are; our duty then is to make sure that the feelings of differences are removed, not get rid of varna dharma itself.

One more point must be considered. Even if you concede that the social divisions have caused bitterness among the different sections here, what about the same in other countries? Can the existence of such ill-will in other lands be denied? The differences there, based on wealth and status, cause bitterness and resentment among the underprivileged and poorer sections. In America, it is claimed that all people have enough food, clothing and housing. They say that the Americans are contented people. But what is the reality there? The man who has only one car is envious of another who has two. Similarly, the fact that one person has a bank balance of a hundred million dollars is cause for heart-burning for another with a bank balance of only a million. Those who have sufficient means to live comfortably quarrel with people better off over rights and privileges. Does this not mean that even in a country like the United States there are conflicts between the higher and lower classes of society?

The story is not different in the communist countries. Though everyone is said to be paid the same wages there, they have officers and clerks who do not enjoy the same status. As a result of the order enforced by the state, there may not be any outward signs of quarrel among the different cadres, but jealously and feelings of rivalry must, all the same, exist in the hearts of people. In the higher echelons of power there must be greater rivalry in the communist lands than elsewhere. The dictator of today is replaced by another tomorrow. Is it possible to accord the same status to all in order to prevent the growth of antagonisms? Feeling of high and low will somehow persist, so too the competitive urge.

It seems to me that better than the distinctions prevailing in the West-distinctions that give rise to jealousies and social discord-are the differences mistakenly attributed to the hereditary of vocations. In the old days this arrangement ensured peace in the land with everyone living a contented life. There was neither envy nor hatred and everyone readily accepted his lot.

The different types of work are meant for the good of the people in general. It is wrong to believe that one job belongs to an "inferior" category and another to a "superior type". There is no more efficacious medicine for inner purity than doing one's work, whatever it be, without any desire for reward and doing it to perfection. I must add that even wrong notions about work(one job being better than another or worse) is better that the disparities and differences to be met with in other countries. We are[or were] free from the spirit of rivalry and bitterness that vitiate social life there.

Divided we have remained united, and nurtured our civilization. Other civilizations have gone under because the people of the countries concerned, though seemingly united, were in fact divided. In our case though there were differences in the matter of work there was unity of hearts and that is how our culture and civilization flourished. In other countries the fact that there were no distinctions based on vocations(anyone could do any work) itself gave rise to rivalries and eventually to disunity. They were not able to withstand the onslaught of other civilizations.

It is not practicable to make all people one, nor can everyone occupy the same high position. At the same time it is also unwise to keep people divided into classes that are like water-tight compartments.

The dharmasastras have shown us a middle way that avoids the pitfalls of the two extremes. I have come as a representative of this way and that is why I speak for it: that there ought to be distinctions among various sections of people in the performance of rites but there must be unity of hearts. There should be no confusion between the two.

Though we are divided outwardly in the matter of work, with unity of hearts there will be peace. That was the tradition for ages together in this land-there was oneness of hearts. If every member of society does his duty, does his work, unselfishly and with the conviction that he is doing it for the good of all, considerations of high and low will not enter his mind. If people carry out the duties common to them, however adverse the circumstances be, and if every individual performs the duties that are special to him, no one will have cause for suffering at any time.