There are a hundred thousand aspects to be considered in a man's life. Rules cannot be laid down to determine each and every one of them. That would be tantamount to making a legal enactment. Laws are indeed necessary to keep a man bound to a system. Our sastras do contain many do's and don'ts, many rules of conduct.

There is much talk today of freedom and democracy. In practice what do we see? Freedom has come to mean the licence to do what one likes, to indulge one's every whim. The strong and the rough are free to harass the weak and the virtuous. Thus we recognise the need to keep people bound to certain laws and rules. However the restrictions must not be too many. There must be a restriction on restrictions, a limit set on how far individuals and the society can be kept under control. To choke a man with too many rules and regulations is to kill his spirit. He will break loose and run away from it all.

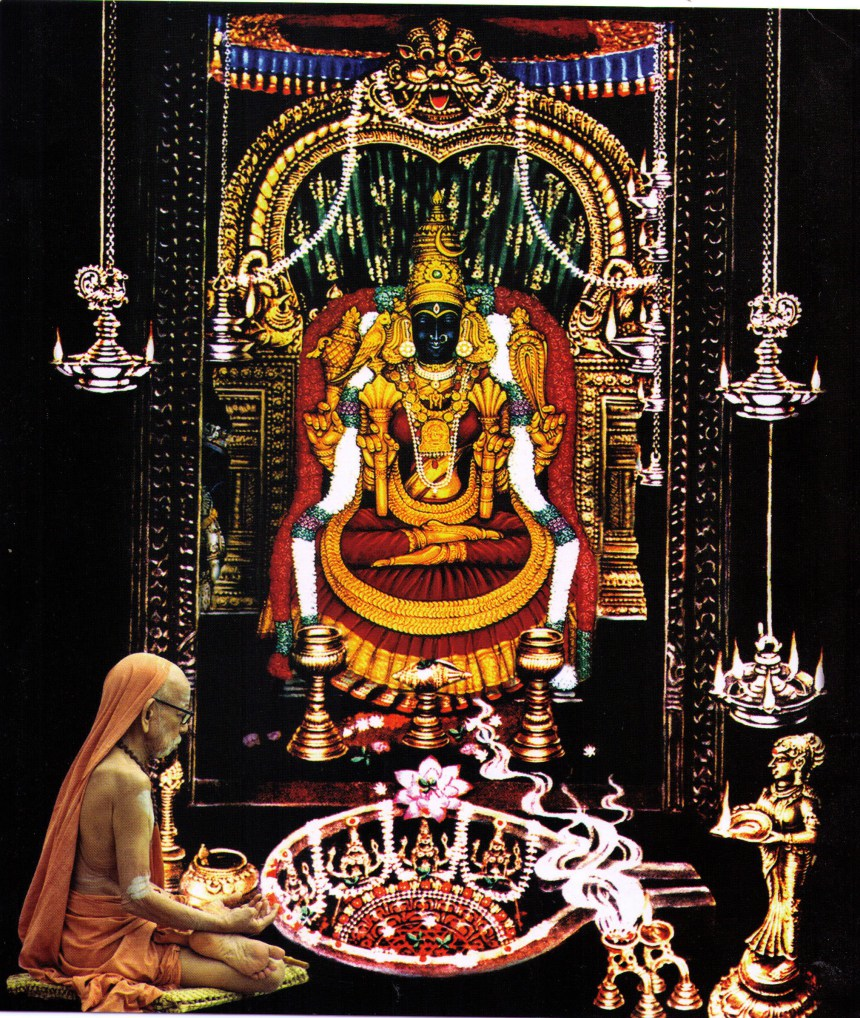

That is the reason why our Sastras have not committed everything to writing and enacted laws to embrace all activities. In many matters they let people follow in the footsteps of their elders or great men. Treating me as a great man and respecting me for that reason, don't you, on your own, do what I do-wear ashes, perform Pujas and observe fasts? In some matters people are given the freedom to follow the tradition or go by the personal example of others or by local or family custom. Only thus will they have faith and willingness to respect the rules prescribed with regard to other matters.

Setting an example through one's life is the best way of making others do their duty or practice their dharma. The next best is to make them do the same on their own persuasion. The third course is compulsion in the form of written rules. Nowadays there are written laws for anything and everything. Anyone who has pen and paper writes whatever comes to his mind and has it printed.

Hindu Dharmasastra has come under attack for ordering a man's life with countless rules and regulating and not allowing him freedom to act on his own. But, actually, the sastras respect his freedom and allow him to act on his own in many spheres. Were he given unbridled freedom he would ruin himself and bring ruin upon the world also. The purpose of the code of conduct formulated by our sastras is to keep him within certain bounds. But this code does not cover all activities since the makers of our sastras thought that people should not be too tightly shackled by the dharmic regulations.

You may feel that with regard to some aspects of life there is an element of compulsion in the sastras, but you may not feel the same when you follow the tradition, the local or family custom or the example of great men. Indeed you will take pride in doing so. This fact is accepted, in the large-heartedness of its author, by the Vaidyanatha-Diksitiyam. Previous works on Dharmasastra shared the same view. The Apastamba-sutra is an authority widely followed. In its concluding part the great sage Apastamba observes: "I have not dealt with all duties. There are so many dharmas still to be learned. Know them from the fourth varna. "From this it is clear that the usual criticism that men kept women suppressed or that Brahmins kept non-Brahmins suppressed is not true. In a renowned and widely accepted dharmasastra such as that of Apastamba women and Sudras are authoritatively recognised to be knowledgeable in some aspects of dharma.

Asvalayana and some other "original" authors of sutras say that the word of women is to be respected in the matter of the arati in weddings and application of paccai. The posts supporting the marriage pandal are installed to the chanting if mantras. Even so, if the servant or worker erecting the pandal has a story to tell about it or some tradition connected with it, you must not ignore it. In this way everyone is respected in the sastras and given what is called "democratic" freedom.

The dharmasastras include the samskaras and other rituals to be performed by the fourth varna. That caste has not been ignored and its duties and rituals are dealt with in the chapters on varnasrama, anhika and sraddha in the Diksitiyam.

The dharmasastras have usually chapters on "acara" and "vyavahara". The first denotes matters of custom and tradition that serve as a general discipline. The second means translating them in terms of outward rites or works.