The Brahmin must keep his body chaste so that its impurities do not detract from the power of the mantras he chants. "Deho devalaya prokto jivah prokto sanatanah. " (The body is a temple. The life enshrined in it is the eternal Lord. ) You do not enter the precincts of a temple if you are unclean. Nothing impure should be taken in there. To carry meat, tobacco, etc, to a temple is to defile it. According to the Agama sastras you must not go to a temple if you are not physically and spiritually clean.

The temple called the body - it enshrines the power of mantras - must not be defiled by an impurity. There is a difference between the home and the temple. In the home it is not necessary to observe such strict rules of cleanliness as in the temple. Some corner, some place, in the house is meant for the evacuation of bodily impurities, to wash the mouth, to segregate during their periods. (In the flat system it its not possible to live according to the sastras). In the temple there is no such arrangement as in a house.

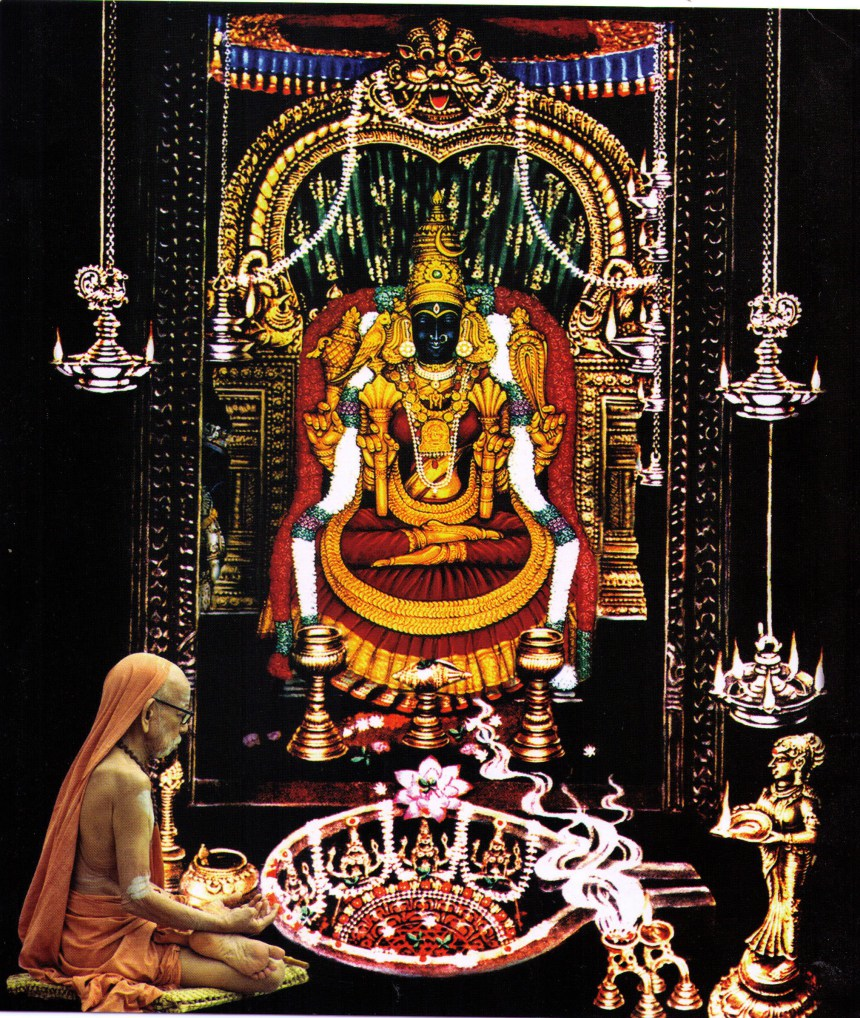

Wherever we live we require houses as well as temples. In the same way our body must serve as a house and as a temple for Atmic work. The Brahmin's body is to be cared for like a temple since it is meant to preserve the Vedic mantras and no impure material is to be taken in. It is the duty of the Brahmin to protect the power of the mantras, the mantras that create universal well-being. That is why there are more restrictions in his life than in that of others. The Brahmin must refrain from all such acts and practices as make him unclean. Nor should he be tempted by the sort of pleasures that others enjoy with the body.

The Brahmin's body is not meant to experience sensual enjoyment but to preserve the Vedas for the good of mankind. It is for this purpose that he has to perform rites like upanayana. He has to care for his body only with the object of preserving the Vedic mantras and through them of protecting all creatures. Others may have comfortable occupations that bring in much money but that should be no cause for the Brahmin to feel tempted. He ought to think of his livelihood only after he has carried out his duties. In the past when he was loyal to his Brahminic dharma the ruler as well as society gave him land and money to sustain himself. Now conditions have changed and Brahmin today has to make some effort to earn his money. But he must on no account try to amass wealth nor must he adopt unsastric means to earn money. Indeed he must live in poverty. It is only when he does not seek pleasure and practices self-denial that the light of Atmic knowledge will shrine in him. This light will make the world live. The Brahmin must not go abroad in search of fortune, giving up the customs and practices he is heir to. His fundamental duty is to preserve the Vedic mantras and follow his own dharma. Earning money is secondary to him.

If the Brahmin keeps always burning the fire of mantras always burning in him, there will be universal welfare. He must be able to help people in trouble with his mantric power and he is in vain indeed if he turns away a man who seeks his help, excusing himself thus: "I do the same things that you do. I possess only such power as you have."

Today the fire of mantric power has been put out (or it is perhaps like dying embers). The body of Brahmin has been subjected to undesirable changes and impure substances have found a place in it. But may be a spark of the old fire still gives off a dim light. It must be made to burn brighter. One day it may become a blaze. This spark is Gayatri. It has been handed down to us through the ages.