More than 20 years ago, I said in an article in The Illustrated Weekly of India that "Hindus know less about their religion than Christians and Muslims know about theirs". Wanting to verify the statement, my editor Sardar Khushwant Singh asked my colleagues (most of them were Hindus), in schoolmasterly fashion, to name any four Upanishads. For moments there was silence and it was a Muslim lady member of the staff who eventually responded to the editor's question by "reeling off" the names of six or seven Upanishads.

Why are "educated" Hindus ignorant about their religion? Is it their education itself that has alienated them from their religious and cultural moorings? If so it must be one of the tragic ironies of the Indian condition. The Paramaguru himself speaks of our ignorance of the basic texts of our religion (Chapter 1, Part Five): "We must be proud of the fact that our country has produced more men who have found inner bliss than all other countries put together. It is a matter of shame that we are ignorant of the sastras that they have bequeathed to us, the sastras that taught them how to scale the heights of bliss. Many are ignorant about the scripture that is the very source of our religion -- they do not know even its name... Our education follows the Western pattern. We want to speak like the white man, dress like him and ape him in the matter of manners and customs..."

The fact is that during the past two or three centuries Hindus have gone through a process of de-Hinduization which in some respects is tantamount to de Indianization. Various other reasons are given as to why Hindus do not have a clear idea of their religion. One is that it is not a religion in the sense the term is usually understood. Another is that it is not easily reduced to a catechism. A third reason is that, unlike other faiths, it encompasses all life and activity, individual, social and national, and all spheres of knowledge. Hindu Dharma is an organic part of the Hindu. It imposes on him a discipline that is inward as well as outward and it is a process of refinement and inner growth. Above all it is a quest, the quest for knowing oneself, for being oneself.

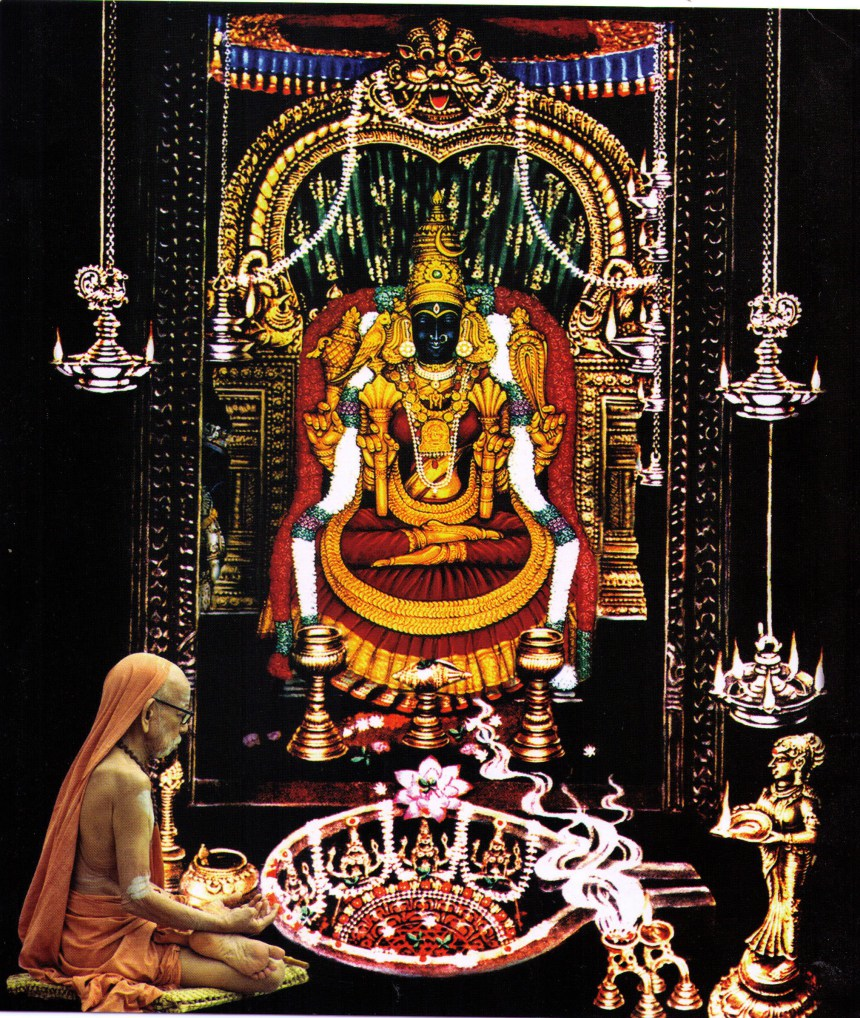

Hindu Dharma, it must be remembered, is but a convenient term for what should ideally be known as Veda Dharma or Sanatana Dharma, the immemorial religion. Indeed, it might be claimed with truth, that this Dharma is more than a religion, that it is an entire civilization, the story of man from the very beginnings of time to find an answer to the problems of life, the story of that greatest of all adventures, that of the human spirit trying to discover its true identity. "From our total reactions to Nature," says J.W.N. Sullivan, "Science selects a small part only as being relevant to its purpose..." Everything is relevant to Hinduism because its "purposes" is to know the Truth in its entirety, not fractions of truth that may have their own purposes but not the Great Purpose of knitting together everything to arrive at the ultimate knowledge. It needs a master to speak about such a religion. We must consider ourselves blessed that we had such a master living in our own time, I mean the Sage of Kanchi, Pujyasri Chandrasekharendra Saraswati Swami, to teach us our Dharma. He was no ordinary master, but a Master of Masters.

This Great Master's discourses on Hindu Dharma, included in Volumes I and II of Deivattin Kural, are divided into 22 parts (there are two appendices in addition) in this book. There is, however, 'nothing rigid about this arrangement and we have here a single great stream that takes us through the variegated landscape that has come to be called Hinduism. To vary the imagery, it is a vast canvas on which the Paramaguru portrays the Hindu religion and it is a luminous canvas and there is nothing garish about the colors he dabs on it.

The Great Acharya does not lecture from a high pedestal. Out of his compassion for us he speaks the language that everybody understands. (We must here acknowledge our profound indebtedness to Sri Ra. Ganapati, the compiler of Deivattin Kural, and Sri A. Tirunavukkarasu, the publisher, for having preserved the Sage of Kanchi's light of knowledge and wisdom for posterity.)

Throughout these discourses we recognize the Great Swami's synaptic vision. He sees connections where others see only differences. Is this not the special quality of a seer, the special quality of a mystic, who refuses to see things in compartments? Indeed, during the long decades during which Sri Chandrasekharendra Saraswati Swami was the Sankaracharya of Kanchi Kamakoti Pitha he was a great unifying force, a great civilizing influence. The manner in which he braids together the karmakanda and jnanakanda of the Vedas is indeed masterly. So too the way he presents the message of the Vedas or the essence of the Upanishads. Here we have something like the architectonics of great music or of a great monument like the Kailsanatha temple of Ellora or the Brhadisvara temple of Tanjavur. The Paramaguru takes all branches of knowledge in his stride, linguistics, astronomy, history, physics. He combines ancient wisdom with modern concepts like those of time and space -- he is aware, though, that some of these concepts are not new to our own scientific tradition. All the same, it must be noted that he does not speak what is convenient for today but what is true for all time.

It is difficult to summarise the ideas of our religion or to present the teachings of our Master in a few words. But it is necessary to underline certain points. For instance, the message of the Vedas on which Hindu Dharma is founded. "The Vedas hold out," declares the Paramaguru, the ideal of liberation here itself. That is their glory. Other religions hold before people the ideal of salvation after a man's departure for another world." To repeat, the ultimate teaching of the Vedic religion is liberation here and now. After all, what is the purpose of any religion? Our Acharya answers the question: "If an individual owing allegiance to a religion does not become a jnanin with inward experience of the truth of the Supreme Being, what does it matter whether that religion does exist or does not?"

"That thou art," is the great truth proclaimed by the Vedas. But how are you to realize the truth of "That"? Our Master's answer is: "Now itself when we are deeply involved in worldly affairs." In fact he tells us the practical means of becoming a jivanmukta, or how to be liberated in this life itself. After all, he was a jivanmukta himself and he speaks of truths not from a vacuum but from actual experience. That reminds one of the special feature of Hindu Dharma which is that it contains the practical steps to liberation; in other words Hinduism leads one to the Light in gradual stages. Critics call this Dharma ritual-ridden without realizing that the rituals have a higher purpose, that of disciplining you, cleansing your consciousness, and preparing you for the inward journey. In a word, chitta - suddhi is the means to a higher end. From work we must go to worklessness. The Paramaguru's genius for synthesizing ideas is demonstrated in the way he weaves together karma, bhakti, yoga and jnana.

In our Vedic religion, individual salvation is not --- as is often alleged --- pursued to the neglect of collective well-being. "The principle on which the Vedic religion is founded," observes the Sage of Kanchi "is that a man must not live for himself alone but serve all mankind." Well, varna dharma in its true form is a system according to which the collective welfare of society is ensured. As expounded by the Paramaguru, we see it to be radically different from what we are taught about it in school. Critics call caste a hierarchic and exploitative arrangement. But actually, the system is one in which the duties of each jati are interlinked with those of others. In this way society is knit together, leaving no room in it for jealousies and rivalries to arise. One point must be specially noted: the Great Acharya lays stress again and again on the fact that no jati is inferior to another jati or superior to it.

In the varna dharma, as explained by our Master, the Brahmin does not lord it over other communities. Why do we need Brahmins at all? To preserve the Vedic dharma, to keep alive the sound of the Vedas which is important for the well-being not only of all Hindus but of all mankind. This duty can be performed only on a hereditary basis by one class of people. The Great Acharya goes to the extent of saying that we do not need a class of people called Brahmins if they do not serve other communities, indeed mankind itself, by truly practicing the ancient Vedic dharma. To paraphrase, if a separate class called Brahmins must exist and it must exist is not for the sake of this class itself but for the ultimate good of mankind. The Paramaguru, makes an impassioned plea to Brahmins to return to their dharma. He also points out that in varna dharma, in its ideal form, there are no differences among the jatis economically speaking -- all of them live a simple life, performing their duties and being devoted to the Lord.

It is varna dharma that has sustained Hindus or Indian civilization for all these millennia, observes the Paramaguru. And all our immense achievements in metaphysics and philosophy, in literature, in music, in the arts and sciences must be attributed to it. Above all, it is varna dharma that has made it possible for this land to produce so many great men and women, so many saintly men, who have been the source of inspiration for people all these centuries. Now this system has all but broken up and with it we see the decay of the nation.

There are so many other matters on which the Sage of Kanchi speaks -- for example, conducting an upanayana or a marriage meaningfully. He speaks with eloquence about our ideals of marriage and condemns dowry, describing it as an evil that undermines our society. There are, then, moving discourses on philanthropy, love and so on in which we see the Great Master as one who is concerned about the happiness of all, as one whose heart goes out to the poor and the suffering. His short discourses like "Outward Karma - Inward Meditation" or "Karma --the Starting Point of Yoga" encapsulate his philosophy with power and beauty. And the message of Advaita runs like a golden thread all through the book.

Altogether in these discourses we come face to face with a Great Being who is beyond time and space and we experience the "oceanic feeling", a term (originally French) coined by Romain Rolland and made familiar by Sigmund Freud. To us the Sage of Kanchi means an ocean of wisdom and an ocean of compassion. To think of him is to sanctify ourselves however unregenerate we may be. I must now, in all humility, pay obeisance to Pujyasri Jayendra Saraswati Swami and Pujyasri Sankara Vijayendra Saraswati Swami and seek their blessings Sri Mettur Swamigal, gentle, devout and learned, has been a source of inspiration to me in my work.

I am thankful to Sri P.S. Mishra, Chief Justice of Andhra Pradesh, for his learned Foreword.

The venerable Sri A. Kuppuswami, who is a spry 84 and who served his Master, the Sage of Kanchi with devotion for almost a lifetime, read the typescript of this book running into more than 1,000 pages and made valuable suggestions. I have always relied on him for advice and I am grateful to him for his Introduction, although I feel I don't deserve a bit the appreciative references he has made to me.

I am indebted to Sri V. Sivaramakrishnan, Associate Editor of Bhavan's journal, for reading the proofs. With his practised eye he detected a number of errors - he also suggested a number of improvements. I must add that Sri Sivaramkrishnan has himself written a book based on the Sage of Kanchi's discourses on Sanskrit and Tamil poets and their works.

The Kamashi Seva Samithi lost one of its stalwarts in the death of its Secretary, Sri V. Krishnamurthi. For most of us the Samithi meant Sri Krishnamurthi and Sri Krishnamurthi meant the Samithi. Members of the Samithi and devotees of the Sage of Kanchi were distraught by his passing but they find consolation in the thought that he must be still be serving the lotus feet of his Master.

Sri P.N. Krihnaswami, Chairman of the Samithi, brought me cheer whenever I felt depressed about the progress of the book. I look upon him as a model of devotion to the Lord and service to fellow-men. So many others belonging to the Samithi have helped me in my work like Sri R.S. Mani, Sri V. Narayanaswami, Captain N. Swaminathan, Sri B. Ramani, and Sri A.G. Ramarathnam.

Dr W.R. Antarkar, a distinguised Sanskrit scholar, has laid me under a deep debt of gratitude by giving the once-over to the Sanskrit part of the main text. But he is not to be held responsible for mistakes, if any, that still remain uncorrected. I must also thank Sri L.N. Subramanya Ghanapathi, Dr R. Krishanmurthi Sastrigal , Sri S. Lakshminarayana, Srimati (Dr) Visalakshi Sivaramkrishnan and Sri V. Ramanathan for their assistance.

Thanks are particularly due to Siromani R. Natrajan, of Manjari fame, for his help in preparing the Tamil Glossary. He checked the notes I had made and added copious notes of his own. Owing to pressure on space all the material povided by him could not be incorporated. I also owe a debt of gratitude to Srimathi Bhavani Vanchinthan, a gifted Tamil teacher, for "double-checking" the glossary and to Srimati Saroja Krishnan for her help.

Mrs. Margaret Da'Costa converted my typescript into computer format in record time. I am thankful to her as well as to Kumari Sandhya Ganapahty: this dedicated young lady worked day and night for nearly three months to carry out my corrections. Sri R.Ganapathy gave his daughter a helping hand. There were also inputs by Sri R.S. Mani and Sri N. Ramamoorthy.

I must thank Sri S. Ramakrishan, Executive Secretary of Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, for the readiness which he agreed to publish HIndu Dharma and for his unfailing courtesy, encouragement and coooperation. I must acknowledge the help received from other officials of the organisation like Sri A.P. Vasudevan, Sri C.K. Venkataraman and Sri P.V. Sankarankutty.

I am grateful to Sri Atul Goradia of Siddhi Printers for the fine job of work he has done in printing this book. He is remainded unfazed by all the problems encountered in the course of the production of this work.

In all humuility I place Hindu Dharma as an offering at the sacred lotus feet of Pujyasri Chandrasekharendra Sarasvati Swami. As one who has miles to go to become jnanin, I can look upon Mahaguru only in the form I knew him before he attained videhamukti. The dvita-bhava, it is said, is the appropriate attitude in which one expresses one's devotion to one's guru. Our Great Master is the Infinite dissolved in the Infinite. But do we not separate the Infinite from the Infinite to meditate on it and to worship It as the Saguna Brahman? It is thus that I adore the lotus feet of the Mahaguru. As the Upanishads proclaim, "Purnasya purnamadaya purnmevavsisyate."

"CHINNAVAN"

Bombay, May 19, 1995